Experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider reveal how surprisingly fragile atomic nuclei can emerge from extreme particle collisions that briefly recreate conditions hotter than the Sun’s core. The study shows that deuterons and their antimatter counterparts are not formed in the most violent moments, but arise later from the decay of short-lived particle states as the system cools. Credit: Stock

Researchers from TUM, working at CERN, have made a groundbreaking discovery that reveals how deuterons are formed.

Another long-standing question in particle physics has been answered. Scientists working with the ALICE experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), led by researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), have directly observed how some of the simplest atomic nuclei and their antimatter equivalents are created in extreme particle collisions.

These nuclei, known as deuterons and antideuterons, each consist of only two building blocks, making them ideal probes for studying the most fundamental forces of nature.

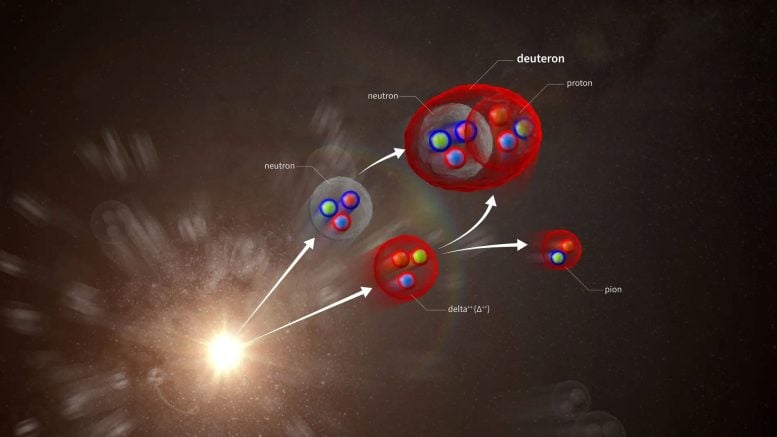

At the heart of every atomic nucleus is the strong interaction, the force that binds protons and neutrons together. In the new study, researchers found that the protons and neutrons needed to form deuterons are not present from the beginning of a collision. Instead, they emerge from the decay of extremely short-lived, high-energy particle states (so-called resonances) and then combine into light nuclei. The same process applies to their antimatter counterparts.

The results were published in the leading journal Nature.

The experiments take place in proton collisions at the LHC at CERN, where temperatures briefly soar to more than 100,000 times hotter than the center of the Sun. Under such violent conditions, delicate objects like deuterons and antideuterons were expected to fall apart almost instantly. After all, a deuteron is made of just one proton and one neutron, held together by a relatively weak binding force.

Despite this, these light nuclei have been observed repeatedly in past experiments. The new measurements now show why: about 90 percent of the observed (anti)deuterons form through this resonance decay pathway, and they appear later, after conditions begin to cool.

Better understanding of the universe

TUM particle physicist Prof. Laura Fabbietti, a researcher in the ORIGINS Cluster of Excellence and SFB1258, emphasizes: “Our result is an important step toward a better understanding of the ‘strong interaction’ – that fundamental force that binds protons and neutrons together in the atomic nucleus. The measurements clearly show: light nuclei do not form in the hot initial stage of the collision, but later, when the conditions have become somewhat cooler and calmer.”

Schematic artistic imaging of the formation of deuterons. Credit: ALICE/TUM

Maximilian Mahlein, a researcher at Fabbietti’s Chair for Dense and Strange Hadronic Matter at the TUM School of Natural Sciences, explains: “Our discovery is significant not only for fundamental nuclear physics research. Light atomic nuclei also form in the cosmos – for example, in interactions of cosmic rays.

They could even provide clues about the still-mysterious dark matter. With our new findings, models of how these particles are formed can be improved, and cosmic data interpreted more reliably.”

Further information

CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) is the world’s largest research center for particle physics. It is located on the border between Switzerland and France near Geneva. Its centerpiece is the LHC, a 27-kilometer-long underground ring accelerator. In it, protons collide at nearly the speed of light.

These collisions recreate conditions similar to those that existed just after the Big Bang – temperatures and energies that do not occur anywhere in everyday life. Researchers can thus investigate how matter is structured at its most fundamental level and which natural laws apply there.

Among the experiments at the LHC, ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) is specifically designed to study the properties of the so-called strong interaction – the force that holds protons and neutrons together in atomic nuclei. ALICE acts like a giant camera, capable of precisely tracking and reconstructing up to 2000 particles created in each collision. The aim is to reconstruct the conditions of the universe’s earliest fractions of a second – and thereby better understand how a soup of quarks and gluons first gave rise to stable atomic nuclei and ultimately to matter.

The ORIGINS Cluster of Excellence investigates the formation and evolution of the universe and its structures – from galaxies, stars, and planets to the very building blocks of life. ORIGINS traces the path from the smallest particles in the early universe to the emergence of biological systems. Examples include the search for conditions that could enable extraterrestrial life and a deeper understanding of dark matter. In May 2025, the second funding phase of the cluster, jointly proposed by TUM and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU), was approved as part of the highly competitive Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments.

The Collaborative Research Center “Neutrinos and Dark Matter in Astro- and Particle Physics” (SFB 1258) focuses on fundamental physics, where the weak interaction, one of the four fundamental forces of nature, is central. The third funding period of the SFB1258 started in January 2025.

Reference: “Observation of deuteron and antideuteron formation from resonance-decay nucleons” by The ALICE Collaboration, , 10 December 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09775-5

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Comments(0)

Join the conversation and share your perspective.

Sign In to Comment