Evolution unfolds in a world that is constantly changing, but not all kinds of change shape populations in the same way. Using a large-scale computer model, researchers replayed evolution across many different fluctuating environments and discovered that variability can either help or hinder adaptation, depending on its nature. Credit: Stock

Repeated environmental changes can lead evolution in unexpected directions, and research from Vermont shows that studying a single population does not capture the full story of an entire species.

All forms of life exist in environments that are constantly shifting. Seasons change, wet years follow dry ones, and conditions that once favored survival can quickly disappear. Because of this, it is clear that plant and animal populations are continually forced to adapt, says University of Vermont scientist Csenge Petak. What remains uncertain is how these ongoing environmental changes influence the course of evolution itself.

“Do populations benefit from lots of environmental fluctuations, making new generations more prepared to face future changes,” she wondered, “or are they impaired, forced to readapt again and again, never reaching the heights of fitness that the same populations in a stable environment could achieve?”

To investigate this question, Petak teamed up with University of Vermont computer scientist Lapo Frati, along with two additional UVM researchers and a collaborator from the University of Cambridge. Together, they designed a novel study built around a powerful computer model capable of simulating thousands of generations of digital organisms. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), were unexpected.

“We found remarkable variation in how populations evolved in variable environments,” they write. “In some cases, changing the environment helped populations find higher fitness peaks; in others, it hindered them.”

Impossible to test in a lab

“Researchers often watch the long-term trajectory of one population in a specific environment, says Frati. “We picked an array of environments and see how the specifics of each one influence the trajectory of many populations.”

Why this matters becomes clearer when looking at real-world examples. Imagine two populations of fruit flies. A group living in the United States may evolve traits suited to large seasonal temperature swings, while a population in Kenya faces a very different challenge, alternating between long droughts and periods of heavy rainfall. These distinct patterns of environmental change can push evolution in very different directions, even within the same species.

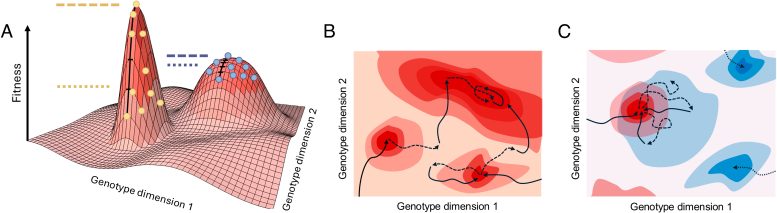

Schematic representation of fitness landscapes. (A) Maximum (dashed) and average (dotted) population fitness on narrow (yellow) versus wide (blue) peaks; larger gaps indicate narrower optima. (B) Population trajectories in a periodically changing environment across visible (solid) and unseen (dashed) fitness landscapes, with wider peaks more likely to be found and retained.

(C) Conceptual “trapping” in variable environments, where evolution in one condition prevents access to higher-fitness peaks available under static conditions. Credit: PNAS, Csenge et al.

“Temperature fluctuations might promote better adaptation to both cold and warm seasons,” Petak explains. “But repeated cycling between dry and wet seasons might actually impede adaptation to drought, forcing the population to ‘restart’ evolution after they experience a long period of rainfall—leading to worse traits than in populations exposed only to drought.”

These are two populations of the same species trying to cope with a fluctuating environment. And yet different types of fluctuations may lead to radically different evolutionary outcomes, where one group of flies benefits from the alternating conditions while the other is harmed.

Replaying Evolution at Scale

“What’s exciting about this study is that we replayed evolution hundreds of times. This gave us a bird’s-eye view of how evolution played out across many different environments—something that would be impossible to test in the lab,” said senior author Melissa Pespeni, a professor of biology at UVM.

“The biggest takeaway for me is that starting point really matters. A population’s history shapes how high it can climb and how hard the path is to get there, which means we can’t assume one population represents an entire species.”

The team’s discovery may have implications for pressing human concerns. For example, it’s important to understand whether species will be able to adapt quickly enough to survive global climate change.

And bacteria repeatedly evolve new ways to resist the antibiotics we invent. And yet scientists often study only a single population in one specific type of fluctuating environment—and then draw broad conclusions about how environmental change will hurt or harm that species.

“Computational models, like ours, can be used to formulate new hypotheses about real biological populations,” Petak says.

To conduct their study, the UVM team built artificial organisms and placed them in many different types of shifting environments. These digital environments mimic alternating conditions in nature, like hot-cold cycles and drought-rainfall swings. “What is new in our work,” Petak explains, “is that instead of studying evolution in just one variable environment, we created 105 different variable environments.

This allowed us to systematically compare how populations evolve across many distinct scenarios.”

AI implications

This finding has implications beyond biology—it may inform open questions in AI and machine learning as well. Artificial intelligence systems often struggle to learn new tasks without forgetting old ones. UVM computer scientist Nick Cheney, a co-author, draws direct parallels between evolution in nature and AI training.

“AI systems have traditionally been built narrowly around solving one specific question,” Cheney says, but new approaches aim for general systems that learn continuously. A fast-growing area of AI research called online continual learning, he says, “beautifully mirrors the ideas explored in this paper around how evolution, learning, and development engage with—and benefit from—variable and dynamic environments.”

For Frati, the implications of the new study about learning—whether in organisms or circuits—are exciting. “My research is about meta-learning, the capability of systems to learn to learn,” he says. “In much the same way you cannot properly assess an AI’s ability to learn from focusing on a single subject, this work shows the importance of exploring multiple, diverse yet comparable environments when trying to assess evolvability, the capability of a system to evolve to evolve.”

At the core of this study is the realization that, with evolution, the history and starting point shape the journey, while each traveler will get to a different place depending on the kinds of challenges they face. “Our results show that the choice of variable environment,” Petak says, “can strongly influence the outcome.”

Reference: “The variability of evolvability: Properties of dynamic fitness landscapes determine how phenotypic variability evolves” by Csenge Petak, Lapo Frati, Renske M. A. Vroomans, Melissa H. Pespeni and Nick Cheney, 15 December 2025, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Comments(0)

Join the conversation and share your perspective.

Sign In to Comment