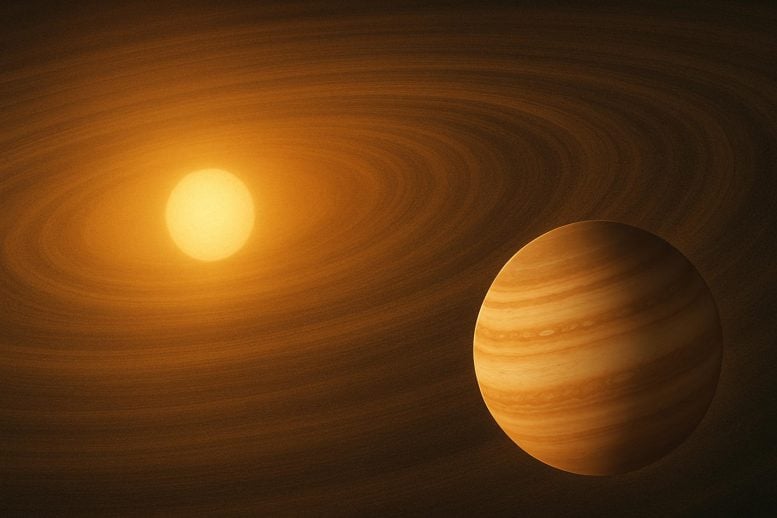

A new timing-based method reveals that some hot Jupiters followed a calm, disk-driven path toward their stars rather than a chaotic one. Their orderly orbits and stable planetary neighborhoods preserve clues to their origins. Credit: SciTechaily.com

The first planet ever found orbiting another star was detected in 1995, and it belonged to a class now known as a “hot Jupiter.” These exoplanets are comparable in mass to Jupiter but circle their stars in just a few days. Scientists now believe that hot Jupiters originally formed far from their stars, similar to Jupiter in our Solar System, and later moved inward.

Two main processes have been proposed to explain this journey: (1) high-eccentricity migration, where gravitational interactions with other objects distort a planet’s orbit before tidal forces near the star gradually make it circular; and (2) disk migration, in which a planet slowly spirals inward while embedded in the protoplanetary disk of gas and dust.

Why Migration Paths Are Hard to Identify

Figuring out which migration route a specific hot Jupiter followed has proven difficult. During high-eccentricity migration, gravitational disturbances can tilt a planet’s orbit relative to the rotation of its star, creating a measurable misalignment.

Over time, however, tidal forces can reduce or erase this tilt. Because of this effect, even a well-aligned orbit does not guarantee that a planet formed through disk migration. For years, astronomers lacked a dependable observational way to distinguish between these two scenarios.

A New Way to Test Planetary Migration

To overcome this limitation, a research team led by PhD student Yugo Kawai and Assistant Professor Akihiko Fukui at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo, introduced a new observational approach that focuses on the timing of high-eccentricity migration itself.

In this process, a planet initially follows a highly stretched orbit before repeated close passes to its star allow tidal forces to round it out. How long this circularization takes depends on factors including the planet’s mass, its orbital period, and the strength of tidal interactions. If a hot Jupiter formed through high-eccentricity migration, this process must have finished within the lifetime of the planetary system. When the researchers calculated circularization times for more than 500 known hot Jupiters, they found about 30 planets that do not meet this requirement—they have circular orbits despite circularization times longer than their system ages.

Signs of Smooth Disk Migration

These planets also show other traits expected from disk migration. Their orbits are aligned with their host stars, suggesting a smooth inward journey rather than a violent gravitational reshuffling. Several of these hot Jupiters are also part of multi-planet systems. Such systems are unlikely to survive high-eccentricity migration, which often destabilizes or ejects neighboring planets.

What These Planets Can Tell Us Next

Finding planets that still retain evidence of how they moved through their systems is essential for understanding how planetary systems develop. Future studies of their atmospheres and chemical compositions may reveal where in the disk they originally formed, offering new insight into the origins and evolution of hot Jupiters.

Reference: “Identifying Close-in Jupiters that Arrived via Disk Migration: Evidence of Primordial Alignment, Preference of Nearby Companions and Hint of Runaway Migration” by Yugo Kawai, Akihiko Fukui, Noriharu Watanabe, Sho Fukazawa and Norio Narita, 7 November 2025, The Astronomical Journal.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Comments(0)

Join the conversation and share your perspective.

Sign In to Comment