This is a Hubble Space telescope image of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS. Hubble photographed the comet on 21 July 21 2025, when the comet was 365 million kilometers from Earth. Credit:

NASA, ESA, D. Jewitt (UCLA); Image Processing: J. DePasquale (STScI)

Researchers at Auburn University have identified a distinctive ultraviolet signature of water in the interstellar comet known as 3I/ATLAS.

For millions of years, a fragment of ice and dust drifted between the stars—like a sealed bottle cast into the cosmic ocean. This summer, that bottle finally washed ashore in our solar system and was designated 3I/ATLAS, only the third known interstellar comet ever observed.

When scientists at Auburn University aimed NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory at the object, they detected something never seen before in this kind of visitor: hydroxyl (OH) gas, which is a clear chemical marker of water. Swift’s space-based telescope was able to capture a faint ultraviolet signal that cannot be detected from the ground, because Earth’s atmosphere blocks most ultraviolet light before it reaches the surface.

Detecting water, through its ultraviolet byproduct hydroxyl, represents a major advance in the study of interstellar comets. In comets from our own solar system, water serves as the main reference point for measuring overall activity and understanding how sunlight drives the release of other gases. It is the chemical standard used to compare the mix of volatile ices inside comet nuclei.

Finding the same indicator in an interstellar object allows astronomers, for the first time, to evaluate 3I/ATLAS using the same framework applied to familiar solar system comets, opening a new path for comparing the chemistry of planetary systems across the galaxy.

Water activity where none was expected

What sets 3I/ATLAS apart is the location at which this water-related activity was observed. Swift detected hydroxyl when the comet was nearly three times farther from the Sun than Earth, well beyond the zone where water ice on a comet’s surface would normally turn directly into gas. The measurements indicate a water loss rate of about 40 kilograms per second, comparable to the flow from a fully open fire hose.

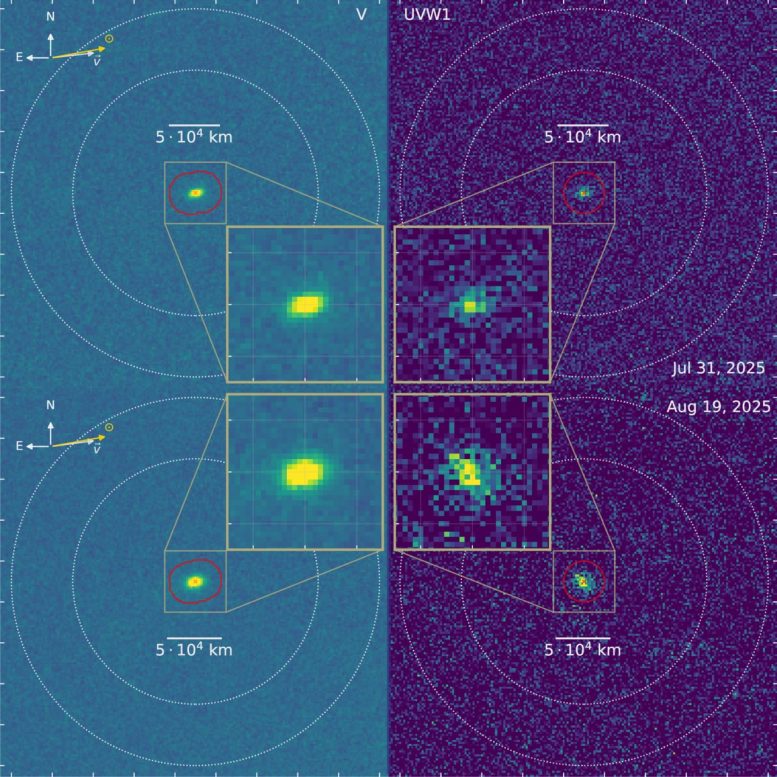

NASA’s Swift Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT) observed interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS during two visits in July and August 2025. The panels show visible-light (left) and ultraviolet (right) images, where the faint glow of hydroxyl (OH) traces water vapor escaping from the comet. Each image combines dozens of short, three-minute exposures, painstakingly stacked to reach total integration times of about 42 minutes in visible light and 2.3 hours in ultraviolet.

Swift’s vantage point above Earth’s atmosphere allowed astronomers to detect these ultraviolet emissions that are normally invisible from the ground. Credit: Dennis Bodewits, Auburn University

At such distances, most comets from the solar system show little to no activity. The strong ultraviolet signal suggests that another process may be responsible, such as sunlight warming small icy grains released from the nucleus, allowing them to vaporize and sustain the surrounding cloud of gas. Similar extended sources of water have been identified in only a few distant comets and are thought to reflect layered ice structures that preserve information about how these objects formed.

So far, every interstellar comet detected has displayed a different chemical profile, revealing a wide range of planetary environments beyond our Sun. Together, these visitors show that the materials that make up comets, especially their volatile ices, can differ substantially from one star system to another. These variations offer clues to how factors such as temperature, radiation, and composition shape the raw ingredients of planets and, potentially, the conditions needed for life.

Seeing ultraviolet signals from space

Catching that whisper of ultraviolet light from 3I/ATLAS was a technical triumph in itself. NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory carries a modest 30-centimeter telescope, but in orbit above Earth’s atmosphere, it can see ultraviolet wavelengths that are almost completely absorbed before reaching the ground.

Free from the sky’s glare and air’s interference, Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope achieves the sensitivity of a 4-meter-class ground telescope for these wavelengths. Its rapid-targeting capability allowed the Auburn team to observe the comet within weeks of discovery—long before it grew too faint or too close to the Sun to study from space.

“When we detect water—or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH—from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from another planetary system,” said Dennis Bodewits, professor of physics at Auburn. “It tells us that the ingredients for life’s chemistry are not unique to our own.”

“Every interstellar comet so far has been a surprise,” added Zexi Xing, postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study. “‘Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each one is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

3I/ATLAS has now faded from view but will become observable again after mid-November, offering another chance to track how its activity evolves as it approaches the Sun. The current detection of OH, reported in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, provides the first clear evidence that the comet is releasing water at large heliocentric distances.

It also shows how a small space-based telescope, free from Earth’s atmospheric absorption, can reveal faint ultraviolet signals that link this visitor to the wider family of comets—and to the planetary systems from which they are born.

Reference: “Water Production Rates of the Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS” by Zexi Xing, Shawn Oset, John Noonan and Dennis Bodewits, 30 September 2025, The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Comments(0)

Join the conversation and share your perspective.

Sign In to Comment