Researchers uncovered that myelin does more than speed up nerve signals, it helps preserve the structure of information as it travels through the brain. When a small, strategic segment of myelin is lost, communication between brain regions becomes unreliable, even if signals still pass through. Credit: Shutterstock

A mouse study reveals that losing a small but critical segment of myelin can disrupt how the brain encodes and transmits information.

Nerve cells are wrapped in a protective coating called (myelin), which enables electrical signals to travel rapidly through the brain. Scientists have long known that this insulation is essential for fast communication, but its role in long-distance signaling has remained less clear. To investigate, Maarten Kole’s research group conducted experiments in mice, focusing on nerve fibers that connect the brain’s outer layer to the thalamus, an important relay center located deep within the brain.

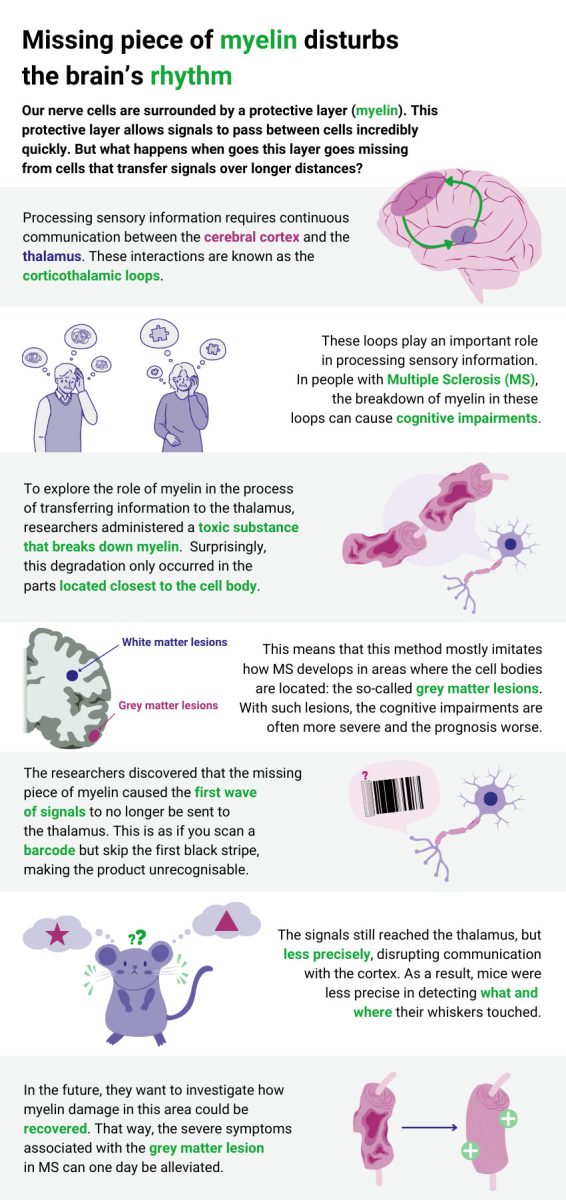

The brain processes sensory input through constant back-and-forth signaling between the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer, and the thalamus. This exchange can be observed when mice use their whiskers to explore their surroundings. Researchers refer to this recurring communication pathway as a corticothalamic loop.

In humans, these loops support sensory perception as well as a wide range of cognitive functions. When myelin is damaged, as occurs in Multiple Sclerosis (MS), this communication can break down, leading to cognitive difficulties such as trouble remembering familiar names.

The nerve cells that are most important for information exchange in these loops are those located in the fifth layer of the brain’s cerebral cortex. “We actually understand these cells very well, but we didn’t know which role myelin played in the process of transferring information to the thalamus,” Maarten Kole, group leader at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, explains.

Targeted myelin degradation

To explore this role, the researchers administered a toxic substance that breaks down myelin. They expected that this would cause the entire nerve fiber to lose its myelin. But instead, the degradation only occurred in the parts located closest to the cell body.

This means that this method mostly imitates how MS develops in areas where the cell bodies are located: the so-called gray matter lesions. With such lesions, the cognitive problems are often more severe and the prognosis worse. In these instances, people with MS can’t orient themselves properly anymore, notice problems when driving, and struggle to recall the names of people familiar to them.

Missing piece of code

The researchers discovered that the missing piece of myelin resulted in slower and less consistent signal transmission to the thalamus. “We had anticipated this, because myelin is known to be essential for fast signal transmission,” Kole explains, “but what was new to us was that we lost the first wave of signals entirely.”

“You could compare it to a barcode in the supermarket: the scanner only recognizes a product if you scan the entire barcode. But if you miss the first piece of myelin, then you’re essentially skipping the first black stripe of the barcode. Because of this, you can’t scan the right product anymore.”

Infographic: missing piece of myelin disturbs the brain’s rhythm. Credit: Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience

Unrecognizable environment

But what is the exact impact of this missing piece of code? When the whiskers of a mouse touch an object, the cells in the brain’s cerebral cortex act as an amplifier of the thalamus. This amplification helps the mouse more accurately determine what and where it’s touching something.

“We saw that this amplification is still happening, but less accurately. Because of that, the communication loop between these two brain areas is disrupted, and the brain loses track. The mouse can still feel something with its whiskers, but it can’t exactly identify when or what,” Kole explains.

What does this mean?

Insight into the anatomy and workings of these specific nerve cells is important for future research. “We’ve known for a while that these cells are wrapped in myelin in a very particular way,” Kole confesses. “It’s one of the few cell types where the first part in particular is so specifically isolated. Now we finally understand why that’s the case.”

This knowledge forms a basis for our understanding of symptoms that develop with gray matter lesions. We know that the brain is continuously generating codes. When myelin on these nerve cells is lost, the codes change, and that communication in the brain is disrupted. This results in cognitive problems, like struggling to orient yourself.

In the future, Kole’s team wants to investigate how myelin damage in this area could be recovered. That way, the severe symptoms associated with the gray matter lesion in MS can one day be alleviated.

Reference: “Layer 5 myelination gates corticothalamic coincidence detection” by Nora Jamann, Jorrit S. Montijn, Naomi Petersen, Roeland Lokhorst, Daan van den Burg, Maayke Balemans, Stan L. W. Driessens, J. Alexander Heimel and Maarten H. P. Kole, 11 December 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66157-1

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Comments(0)

Join the conversation and share your perspective.

Sign In to Comment